The Initial Information Slot

At the head of every piece of ABC notation are several lines of information. This idea is taken from the “standard” ABC notation talked about in the above paragraph. We have the following pieces of information provided:

TUNE TYPE: This refers to the kind of tune we are dealing with e.g. reel, jig, hornpipe, polka, slide etc.

KEY/MODE: The “key/mode” is an important section in these documents and one that you should always pay attention to. Most traditional musicians, when referring to the modality of a tune, will use the term “key” instead of “mode” and the vast majority of current ABC notation at OAIM just uses this term. I have begun using the “mode” signifier as well as this is technically more correct but, regardless of the wording, it relates to the same information

The first part of the information is a letter which determines the quality of the key/mode. This could be anything from A to G with a corresponding sharp (#) or flat (b) symbol. The flat symbol is not to be found on a QWERTY keyboard so hence we make use of the small letter ‘b’. After the key quality the mode is noted. This is usually one of four different modes (Major, Minor, Dorian or Mixolydian). Now please don’t be put off by these terms which may be novel to you. If you understand them, well and good. If not, the next section will provide all of the information you need to know. Here you will find, in brackets, the notes which are altered from the natural scale. So, for example, if you see the key/mode noted as “G MAJOR” and are unfamiliar with what that actually means, just refer to the notes in brackets to help you along. In this case, you will see “(F#)” which is telling you that all of the notes you see in the notation are natural (i.e. not flats or sharps) except for the “Fs” which are ALL F#. I didn’t notate every sharp and flat as it would look too cluttered and also make accidentals less easy to spot. I have refrained from using the mode terms “Ionian” and “Aolian” and, instead, refer to them as “Major” and “Minor” respectively. This is just a matter of simplicity taking precedence over technicalities.

TIME SIG: The time signature refers to the rhythm and timing of the tune. For example, reels, hornpipes and barndances will be in 4/4 or common time. You can expect these kinds of tunes to be notated in groups of four notes. Jigs will be in 6/8 and are written in groups of three notes. Pay attention to slow airs too. It is not possible to accurately notate a slow air as the rhythm is free and up to interpretation. This will be indicated as “FREE RHYTHM” and the notation is merely there for helping with the melodic notes. For slow airs, if a rhythm is indicated it may just be for the sake of writing the melody notes in some structured fashion but is not intended to be followed with any degree of accuracy if followed by the phrase “FREE RHYTHM”.

COMPOSER: The vast majority of tunes at OAIM are traditional tunes. They are 150-300 years old and the composers are unknown. However, some tunes have been written in more recent decades by prolific composers of the music and, to pay heed to their work, I’ve included them where possible.

PARTS AND REPEATS: So after you’re armed with the basic information for the tune, next you will find the first part heading with either (X1) or (X2) written beside it. This simply refers to whether you play the first part straight through and then go into part 2 or if, instead, you go back and repeat part 1 again. The first part is referred to as the A-part and the second part is the B-part. Usually tunes are either played in the AB form (first part once, second part once) or the AABB form (first part twice, second part twice) but some are more unusual and might be played as AAB or ABB.

If a part is to be repeated you may see an alternative ending notated at the end of the part. This will be indicated by a [1 and [2 symbol. On the first pass through the part you play what is notated after [1 and then repeat from the beginning. On the second pass through you disregard what is written after [1 and, instead, play [2 before moving into the next part of the tune.

Many tutors will vary a tune on the second or third time through. I’ve only notated one, basic version of the tune’s melody as taken from the tutor’s simple outline at the beginning of a lesson. I leave it up to you, the student, to focus on the differences that the tutor will guide you through on subsequent repeats.

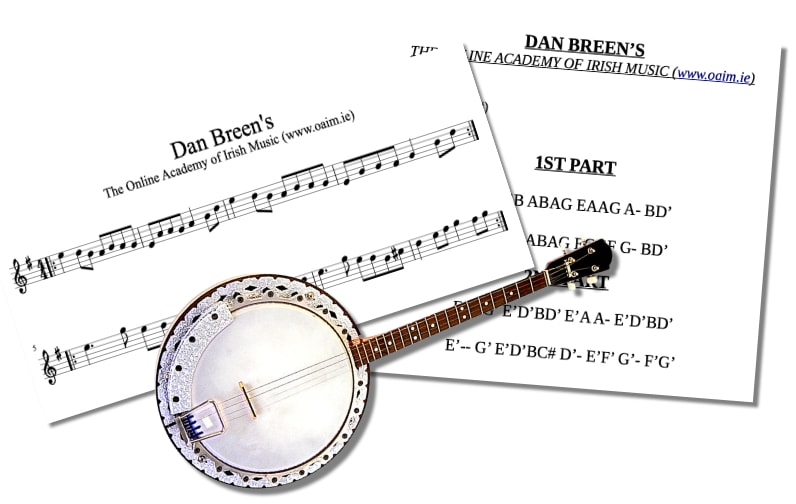

READING THE NOTES

Finally, it’s time to look at the notes themselves. They are straightforward alphabetical letters which refer to each scale degree. As a starting point, let’s look at the note letter D. This refers to an open D string on a fiddle, banjo or mandolin. It is the low D on flute, pipes and whistle. Basically, it’s the D just above middle C on a piano but for instruments like the tenor banjo, which is one octave lower than the fiddle, this is not strictly true. This is the lowest note that can be notated without the use of apostrophes or commas.

For notating the C, B, A and G below this D we use a comma after the note. For example, the note “B,” refers to the B on the G-string on fret four of the banjo or in that position on a fiddle. It is not possible to reach any of these lower notes on the flute, tin whistle or pipes (although certain flutes do have low-C keys as an option). Since the fiddle and banjo cannot go below “G,” (the open G-string) we generally don’t use any lower notes in the Irish music tradition although, occasionally, an accordion version of a tune might slip a note or two below “G,”.

The highest “unpunctuated” note is C. This refers to the C one octave above middle C. It is found on the A-string on a fiddle, banjo (fret 3) and mandolin and is the C natural cross-fingered note on tin whistle and flute. For the D note above this C we use an apostrophe i.e. “D'” and so forth up the scale as far as the next high C’ (above high B on the E string on fiddle, banjo and mandolin). In the very rare circumstances where a tune goes as far as the next octave D, I use two apostrophes to notate it i.e. D”.

Sometimes accidentals are notated also. These will be in three forms: sharp (#), flat (♭) or natural (♮). This means that, although the “key” may stipulate that the only sharps in the tune are F# and C#, the rules are broken at certain points. If a C or F occurs that is not sharp (i.e. it is natural) it will be notated as C~ or F~. Similarly, if the key stipulated that all notes are natural but an F sharp occurs at one point, it will be notated as F#. As would a B flat be notated as Bb if the key otherwise stated that all other Bs were natural. The ‘~’ symbol is not the correct signifier of a natural note in terms of western standard notation but, as the correct symbol was not readily available to me during the compilation of earlier courses, I took the liberty in using the aforementioned symbol. Subsequently, I discovered how to incorporate the correct natural and flat symbols on my word processor so further ABC notation will use them but don’t be confused by the common use of the “~” across the OAIM resources. When an accidental occurs, any repeat occurrences of this note letter are assumed to be of the same quality as the accidental until the end of the bar. From the next bar, the note letter returns to match that of the key. Let’s look at bars 2 and 4 of Chief O’Neill’s Hornpipe as a good example: